How supervision supports practitioner retention and wellbeing

)

Supervision has been of interest to me throughout my career. As an early years practitioner, I have experienced many different forms of ‘supervision’ – from reflective group conversations where needs, behaviours and interactions with the children have been discussed, to more mechanistic one-on-one performance-based discussions. Over the last eighteen years, I have been fortuitous in my personal experiences of supervision as a practitioner researcher and deputy head of the Pen Green Centre for Children and their Families.

The early years sector is facing significant challenges such as recruitment and retention issues, a funding structure that does not enable settings to maintain high quality education and care, and a pandemic that has had serious consequences on the wellbeing of staff, children and their families. I believe that, if done well, supervision could support the wellbeing and mental health of early years practitioners.

But what does supervision mean?

In the 2012 and more recently 2021 statutory framework for the early years foundation stage, the DfE have stated that;

Supervision should provide opportunities for staff to:

- Discuss any issues – particularly concerning children’s development of wellbeing, including child protection concerns

- Identify solutions to address issues as they arise

- Receive coaching to improve their personal effectiveness (DfE 2021, p26)

These strands are echoed by Ofsted (2021) within the early years inspection handbook, writing that;

Inspectors will gather evidence of the effectiveness of staff supervision, performance management, training and continuing professional development, and the impact of these on children’s wellbeing, learning and development. This includes evidence on how effectively leaders engage with staff and make sure they are aware of and manage any of the main pressures on them.

The recognition from Ofsted and the DfE that supervision should consider children’s wellbeing, learning and development, and child protection concerns is significant. Both organisations have recognised how the mechanism of supervision should support the practitioners' development of their ‘effectiveness’ – making links to training and professional development, as well as stimulating reflectiveness in leaders as to how they can relieve pressures on the practitioners.

I have always been encouraged to see the term as ‘super – vision’ (John, 2007). Framing it this way emphasises the need of the other person within the process of supervision, stressing the importance of both the supervisor and supervisee. I feel that in 'super – vision' it is important to create a space where you can focus on the challenges of everyday practice and life. How alongside another person you can consider what might be going on and the support or training needs we may require, as well as some of the operational processes that may require adaptation for us to work more availably and attentively with children and families.

The Pen Green Model of Supervision

Supervision within the organisation I currently work for has always been highly regarded. Dr Margy Whalley, the founder of Pen Green, embedded supervision within the organisation and today, 40 years on, everyone (including the kitchen and premises team) is provided with supervision. Each individual receives supervision, either monthly or six-weekly, with some staff also having group supervision when they are working together on a specific tasks – for example, working as group facilitators in a particular group with children and their families.

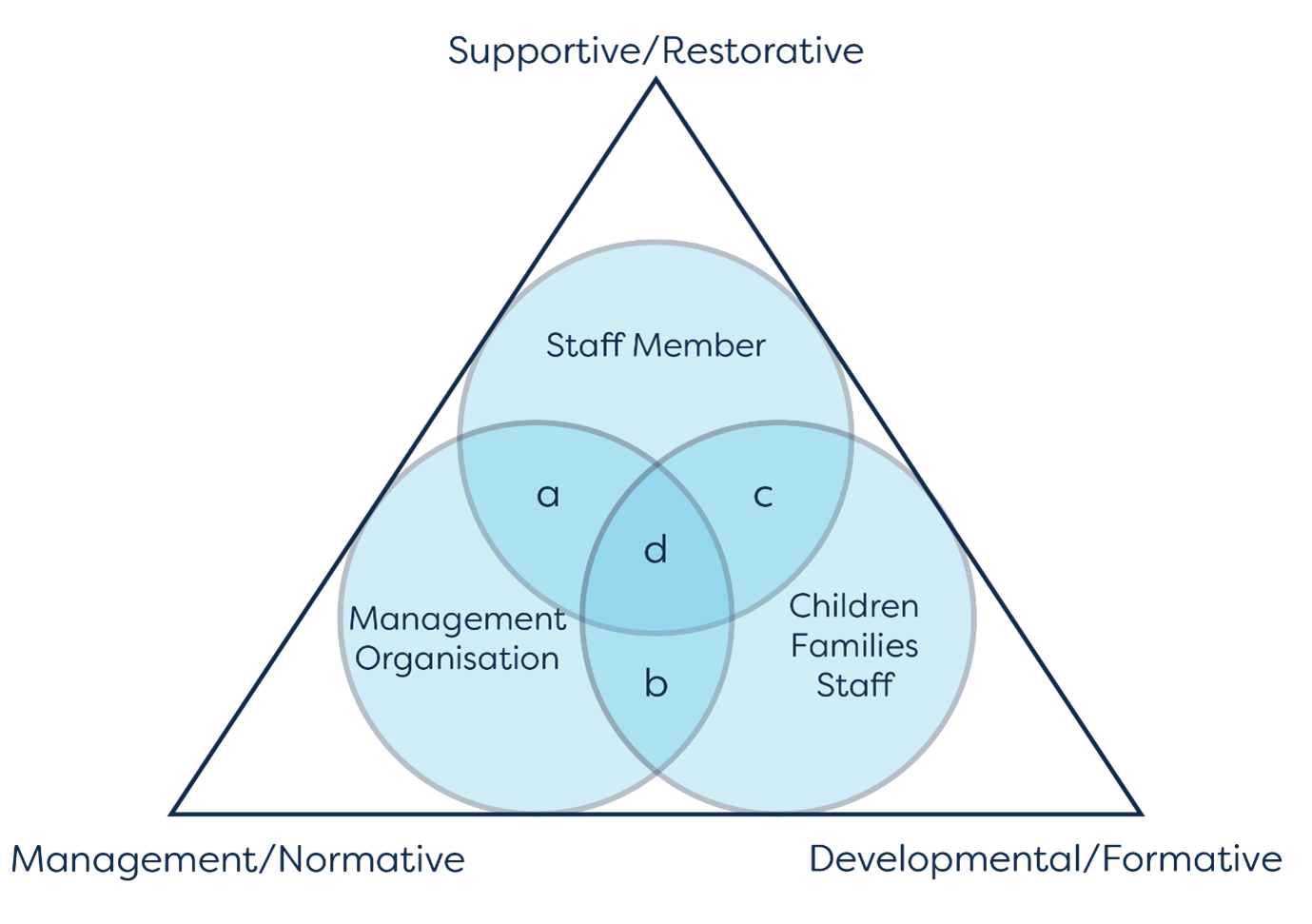

The supervision model we use at Pen Green is based on the Hawkins and Shohet model (2007) and developed by John (2019), highlighted in diagram 1.

Diagram 1 – Model of supervision functions

The model ensures that there is a:

- developmental or formative aspect to supervision, providing an opportunity to discuss skills and understanding.

- management/organisational aspect to discuss aims, principals, policies and standards.

- supportive or restorative aspect, offering an opportunity to discuss how the work is affecting supervisees.

At Pen Green, there are other forums provided to support practitioners to explore the challenges that they face, such as ‘safer practice meetings’. Within these meetings, practitioners can talk about their anxieties, concerns and feelings, and others can contribute. At the end of the discussion, actions are decided upon. There are also regular sessions offered with a child psychiatrist where practitioners can discuss some of the more complex situations they are facing within their work. As a team of senior leaders, we have monthly group supervision with a child and family systems therapist to process some of the organisational issues.

Reduction in burnout and retention of staff

Shohet et al (2020) highlight how relational supervision creates a reflective space which can ‘reduce burnout and restore joy and creativity’ (p12). I know that as a lead in an early years setting, supervision has prevented staff from leaving. It's about recognising the importance of your staff team and ensuring we consider the everyday challenges they face in their personal and professional lives to support their mental health and wellbeing. It keeps practitioners in their role and retains them.

I recognise how privileged I am to work in an organisation that values the supervisory process in such regard. I believe that these processes keep us safe and enable us to be actively ‘available’ and ‘attentive’ to the children and families we support.

-

)

Felicity Dewsbery

Deputy head, Pen Green Centre for Children and their Families